Mike Duignan, University of Surrey

Japanese Olympics minister Tamayo Marukawa has confirmed that, due to COVID, no spectators will be allowed to attend Tokyo 2020. This comes after initial announcements in March 2021 that no international tourists would be allowed to enter Japan for the events which are scheduled to open on July 23.

No visitors means no income. This is, of course, an economic setback for Japan, but specifically for tourist attractions and local businesses often prepared for a spending bonanza.

Capturing tourist spending in and around the live events of the games plays a key role in the return on investment injected by the government and taxpayers into making the games happen in the first place. The total cost of hosting currently stands at US$15.4 billion (£11.1 billion). This will compound the impact COVID-19 has had on the Japanese economy, which shrank by 4.8% in 2020.

Tourism was the primary justification for hosting. Both the government and the public are acutely aware of how important the Tokyo 1964 games were, in terms of revitalising and reconstructing Japan’s infrastructure after the second world war.

From the construction of venues like the Nippon Budokan judo centre, repurposed for Tokyo 2020, to transport networks, including the Shinkansen bullet train, the 1964 games triggered key improvements to the built environment. This in turn has become central to Japan’s tourism industry.

Furthermore, Tokyo 1964 were the first Olympic games to be broadcast live in the history of the games. Footage beamed to between 600 million and 800 million spectators worldwide showcased the city and its cultural assets.

In his 2016 book The Games, sports writer, broadcaster and sociologist David Goldblatt argues that the 1964 games were “the single greatest act of collective reimagining in Japan’s post-war history”. This illustrates how hosting large-scale events can contribute to long-term economic growth and drive tourism ambitions.

The city of Tokyo expected to welcome over 40 million foreign visitors for the 2020 games. An aggressive tourism development strategy put in place, long before COVID hit, was one of the structural reforms the then-prime minister, Shinzo Abe, introduced to fuel future economic growth.

Structural reforms

A series of ecological shocks contributed to catalysing these reforms. The first was the 2011 earthquake. Known as the great Tohoku earthquake, it triggered the tsunami that devastated large swathes of north-eastern Japan and led to the nuclear meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi power plant, rendering the area uninhabitable and off-bounds to tourists.

My recent research has shown how this left Japan with a blemished destination brand, in tourism terms. As part of the recovery effort to signal Japan as a safe place to visit, the government embarked on a decade-long marketing and infrastructural campaign to revive the country’s tourism industry.

Safety, however, was only one objective. The primary goal was to rehaul Japan’s tourism industry and reinvent the country as a unique place to visit. To this end, two initiatives were devised: the country-wide EnjoymyJapan campaign. This was supplemented by a global, multilingual online platform intended to showcase the country’s key attractions, assets and experiences, all in one place.

The second, entitled Tokyo, Tokyo, aimed, much like the UK’s This is GREAT Britain Campaign for London 2012, to illustrate the relationship between the old and the new. Posters featured older cultural symbols, from maneki-neko fortune cats to kabuki theatre, alongside Hello Kitty and new-age robotics. Scattered across the city, from billboards to train stations, these rubbed shoulders with official Tokyo 2020 Olympic posters too, illustrating the strategic link between the two campaigns.

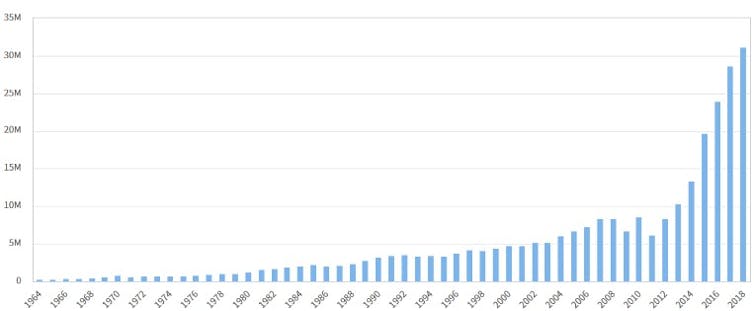

These initiatives appear to have worked. The number of foreign visitors skyrocketed from 7 million international tourists in 2011 to 31 million in 2018. This took Japan from being the 36th most visited country (behind Belgium and Bulgaria) in 1995 to the 11th in 2018.

As a result, citizens at some sites across the country, from the Sasaguri’s Nanzo-in temple to the Golden Gai district in Shinjuku, Tokyo, are reportedly suffering from overtourism. Local living standards have deteriorated, and cultural and ecological damage has been reported.

Broader returns

Beyond the 40 million visitors Japan hoped to reach by 2020 was the goal of 60 million by 2030. COVID of course has put a stop to this. It is not unreasonable to suggest that these campaigns could have easily existed regardless of the Olympics. Arguably, though, without the impetus of hosting, they may have neither come to fruition or received the level of funding required to be successful.

It is worth noting, too, that not all aspects of tourism development are economic. More often than not, these developments are part of a series of social policies too.

Tokyo’s train stations, for example, have been reconfigured to be physically more accessible for those with disabilities. This goes hand in hand with related campaigns, such as the Unity in Diversity leaflets distributed across Japan to change social attitudes towards people with disability. This is significant, as the needs of people with disability have historically been poorly attended to – but this is slowly changing.

Significant economic gains, which tourism scholars refer to as the pregacy (the pre-legacy), have been accrued in the years prior to COVID-19. It is possible, when consumer confidence returns and international travel for pleasure is once again permitted, that Japan’s aggressive tourism development strategy will regain momentum. The benefits of Olympic-led tourism development in the short and long-term are undeniable. Could this be achieved, however, without the billions that hosting an event of this size costs?

Mike Duignan, Head of Department, Reader in Events, and Director of the Observatory for Human Rights and Major Events, University of Surrey

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.