Mia Wege, University of Pretoria; Barend Erasmus, University of Pretoria; Christel Dorothee Hansen, University of Pretoria; Els Vermeulen, University of Pretoria; James Roberts, University of Pretoria; Jean Purdon, University of Pretoria, and Michael John Somers, University of Pretoria

The planned seismic survey off South Africa’s Wild Coast by energy company Shell has unleashed public outrage in the country and beyond. The survey’s aim is to search for oil and gas deposits. Environmental and human rights organisations and fishing communities are trying to block the move in court. The Conversation Africa asked researchers to share their insights on seismic surveys.

What is a seismic survey?

Seismic surveys have been used for at least 50 years in both onshore and offshore mineral and oil exploration. The concept is relatively simple: measure the time it takes for a compression wave (“sound”) to move through solid material, strike a reflecting surface and return to a recorder. This allows the orientation and thickness of layers hidden below the Earth’s surface to be measured, so hidden ore deposits and gas or oil trap structures can be identified.

This negates the need for costly drilling and makes seismic surveys a fast and cost-effective tool in exploration for natural gas or mineral deposits.

Offshore seismic studies use an array of airguns towed on a cable behind a ship to create loud sound pulses, which move through the water to strike and pass into the ocean floor. Though this sound pulse is extremely loud to human ears, it is of far lower amplitude than earthquakes and explosions, and the pulse is not sufficient to cause any physical disruption to faults or structures on the ocean floor. Therefore, it is considered geologically safe.

If a detailed seismic survey confirms the likely presence of gas or the mineral deposit of interest, then it might be followed by drilling test wells.

Is this one unusual?

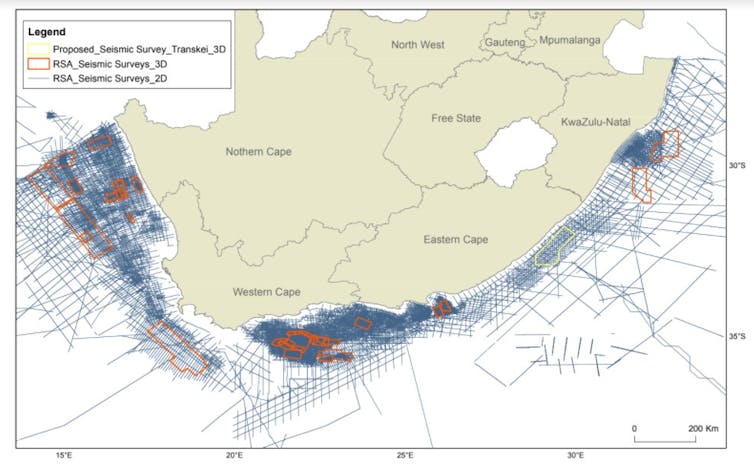

Seismic surveys are not uncommon along the South African coast. The Petroleum Agency of South Africa keeps records of all seismic surveys, and it is clear from this map that many seismic surveys have been done in South African waters, and beyond, since 1967.

Superficially, there does not seem to be anything technically unique about this particular survey, but these details need confirmation from the company that is working with Shell, Impact Oil & Gas.

The main difference is that it has provoked a large public outcry. The concerns are wide and varied, and some of them are in the process of being tested in court. Some have not been successful, while others wait on an outcome.

Seismic surveys have a direct impact on the marine environment – which we unpack below. More importantly, they can also be the precursor of much larger and systematic impacts if the exploration leads to further offshore operations such as drilling.

South African marine biodiversity is unique and valuable in many ways, and the Wild Coast is an especially rich part of that heritage. It’s therefore understandable that people wish to protect it and ask questions about who the true beneficiaries are.

In addition, projects to find new fossil fuel sources are inconsistent with staying within planetary boundaries for a sustainable future. They are at odds with promises made by the South African government during the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26).

What are the effects of marine acoustic seismic surveys?

Seismic surveys, and the subsequent exploitation of oil and gas reserves in much of the world’s oceans, focus on continental shelves, those areas closest to the coast. Here the seafloor is fairly shallow, making it easier (and cheaper) to access oil and gas reserves.

Continental shelves are also productive regions where marine life is the most diverse, where predators hunt for food, or creatures mate and give birth or lay eggs, where corals grow, and ultimately where the most productive fisheries are. Surveys can therefore lead to wide-scale disruption of marine ecosystems, and the value that humans derive from them.

There is a growing body of evidence of the effects of seismic surveys on marine wildlife. These effects are pervasive in marine ecosystems, from the smallest organisms to the largest.

Plankton are very small organisms that form the basis of a healthy marine ecosystem. They consist of phytoplankton (small plants) and zooplankton (small animals). Zooplankton are severely affected by seismic surveys, leading to wide-scale die-off in the vicinity of blasting sites. Since other marine species survive by feeding (directly or indirectly) on zooplankton, this has an effect on the entire aquatic food web.

The critically endangered leatherback turtle, which frequents some areas to be surveyed, is similarly affected by seismic surveys. The Wild Coast is an important area where the young future-breeding individuals spend their time.

Whales and dolphins rely on sound to communicate, navigate and hunt. Generally, the dominant frequencies of seismic airguns (typically below 100 Hz) overlap with those of the communication signals of large baleen whales (10 Hz–1 kHz).

Some seismic surveys also use high frequency sonar mapping, which has been linked to the mass strandings of deep-diving toothed whales. For example in Madagascar 100 melon headed whales stranded and died. The strandings occur because the sonar interferes with their navigational system (echolocation), causing the whales to surface extremely fast. Gas bubbles form in their bloodstream and expand, resulting in decompression sickness, similar to “the bends” that human divers get.

Furthermore, the sound waves generated by seismic surveys may lead to temporary outward migration of wildlife. In another study conducted in the Bass Strait of Australia, it was found that noise exposure during larval development of scallops produced body malformations in nearly half of the larvae and their overall development was delayed.

So how dangerous is this survey?

Despite the examples we’ve given above, the science on the direct and long-term impacts of seismic surveys has not yet provided conclusive answers on many facets of marine ecosystems. But that doesn’t mean there is no basis on which to act. Decisions are often made in the absence of scientific certainty to avoid potentially catastrophic changes in the environment.

The global scientific community has a specific method to assess the state of knowledge in a particular area, to support decision making. It is called a scientific assessment. Among the best known examples are the scientific assessment reports of the International Panel on Climate Change, regularly used in climate policy and decision making.

The same method has also been applied locally to assess the impact of fracking in South Africa’s Karoo region. It is clear that we need a scientific assessment on the impact of seismic surveys to inform the current gaps in South Africa’s National Environmental Management Act and guide the development of new policies.

Until we have the outcomes of such an assessment, the act provides for the application of the precautionary principle in environmental matters and states that:

… a risk-averse and cautious approach is applied, which takes into account the limits of current knowledge about the consequences of decisions and actions.

Other countries have also grappled with seismic survey impacts. Norway, for example, amends its management guidelines in response to findings from ongoing studies. The country does not rely on impact assessments that are years out of date.

Although still needed, it would be short-sighted to focus research on marine environmental impacts and seismic surveys only. The focus should be on the danger to humanity from additional fossil fuel exploration, and the associated increase in the impacts of climate change.

Climate science has matured to the point where there is very strong evidence for the links between life-threatening extreme events such as floods, fires and droughts, and climate change. There are also several new studies that map out feasible and just transitions to reduce our carbon footprint. There really are no good excuses left to continue with any fossil fuel exploration, and certainly not seismic surveys that have an impact on unique and rich marine ecosystems.

Mia Wege, Marine Predator Ecologist and lecturer in Zoology, University of Pretoria; Barend Erasmus, Dean and Professor, University of Pretoria; Christel Dorothee Hansen, Lecturer, University of Pretoria; Els Vermeulen, Research Manager, Mammal Research Institute Whale Unit, University of Pretoria; James Roberts, Associate Professor, Geology, University of Pretoria; Jean Purdon, Marine Biologist, University of Pretoria, and Michael John Somers, Associate Professor, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.