Catherine Kyobutungi, African Population and Health Research Center

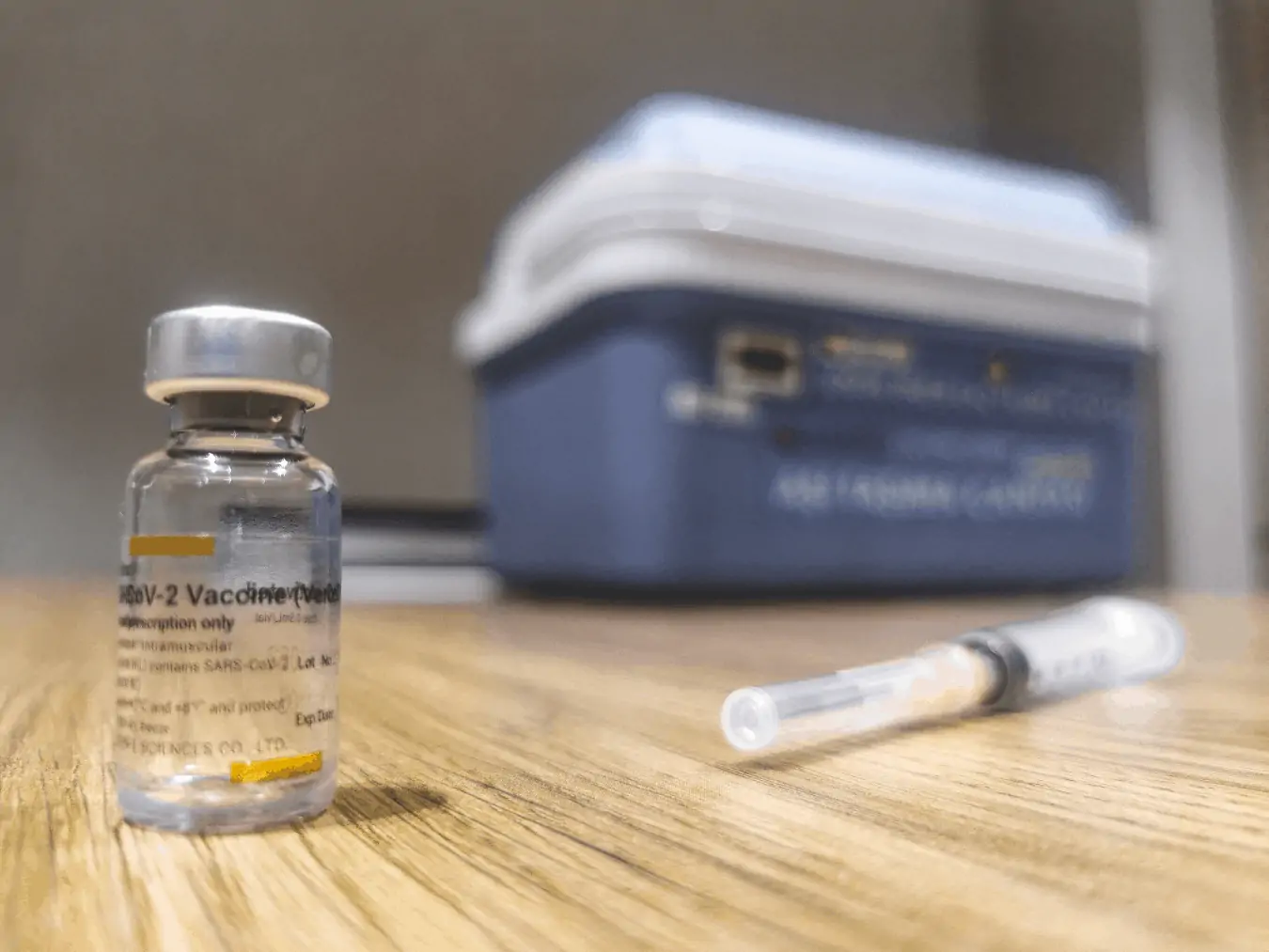

Kenya has started the first phase of its COVID-19 vaccination strategy. This was made possible by the delivery of just over one million AstraZeneca vaccines that arrived in two batches. These came via the global COVAX initiative, which aims to provide equal access to COVID-19 vaccines, and a 100,000 shot donation from the Indian government.

Kenya’s first phase is meant to run until the end of June 2021. The initial plan was to vaccinate high priority groups, such as frontline healthcare workers. A few weeks into the rollout, the target group was expanded to include all Kenyans older than 58 years. This expanded the original target from 1.25 million people to about 3.2 million in the same time period.

But one month into the exercise, just over 280,000 people had been vaccinated. This is slow relative to the targets the government has set. And a lot of catching up will be needed in the next two months.

Some things have gone well. But there are some major gaps.

Parts of the exercise that worked well included the fact that vaccines were distributed quickly to regional depots and all 47 counties. And the exercise is steadily gaining momentum with an increasing number of people being vaccinated each passing week.

But there have been some big teething problems. Countries like Kenya are grappling with two major challenges: access to sufficient doses in light of the global shortage; and vaccine hesitancy.

To improve the rollout, the government has to address both simultaneously. It must balance prioritising high risk groups while encouraging uptake of limited doses.

The government needs to act urgently on both fronts to avoid its healthcare system becoming even more overwhelmed and to save lives.

Increasing access

Getting access to more vaccines is a struggle for most developing countries. But there are things that Kenya can do to narrow the gap between what it has and what it needs.

Firstly, the government needs to develop a comprehensive framework for engaging with the private sector. Private facilities contribute significantly to healthcare provision and it’s common for routine vaccination to be done in private facilities on behalf of, and with support from, the government. For example, the rollout of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in Kenya is currently being done in public and private facilities.

Kenya is currently accessing vaccines exclusively through the COVAX facility – and yet supply to this initiative has been dogged by vaccine nationalism and hoarding.

The private sector has the capacity to access vaccines that are not yet part of the COVAX facility, such as Sputnik V, Sinopharm and Sinovac, albeit in relatively smaller quantities.

This would require the government to negotiate with the private sector based on clearly defined roles and expectations. Any agreed framework must ensure that the vaccines purchased are safe, supplied through approved channels and reasonably priced.

Secondly, Kenya must strengthen its ability to conduct its own reviews of available vaccines. This would reduce the turnaround time for approval and registration.

Countries like Kenya rely on the World Health Organisation (WHO) for approvals. But there are several vaccines widely in use in other parts of the world – such as Sputnik, Sinopharm, Sinovac – that have not yet received emergency use authorisation by the WHO.

Kenya needs to strengthen the capability of the Pharmacy and Poisons Board, which is responsible for approvals. It must be able to conduct its own reviews and expand the pool of vaccines available for purchase. This would mean that Kenya wouldn’t have to wait for the WHO or other regulatory authorities, like the European Medicines Agency, to approve vaccines.

When it comes to increasing uptake, the government needs to up its game in putting out information about vaccination sites and scheduling. And it needs to address issues such as queue jumping and overcrowding in high uptake areas such as Nairobi. There have also been cases of stock running out in high uptake areas while vaccines lie unused in some counties.

Tackling hesitancy

Vaccine hesitancy, specifically against the COVID-19 vaccine, has been spreading in Africa. Fears and suspicion about COVID-19 vaccines have not been helped by reports linking the AstraZeneca vaccine to the development of blood clots. AstraZeneca is currently the only available vaccine in Kenya.

The government recognised the danger of vaccine hesitancy even before the rollout began, listing it as a risk in the national rollout plan. The communication around this was supposed to start before the vaccines arrived, but it didn’t.

Evidence of this scepticism has become clear in the slow uptake in the original priority groups.

To counter this, the government should be alive to areas where there is vaccine enthusiasm – such as Nairobi – and harness this in preparation for future phases when more vaccines are available.

This is because the slow uptake may not entirely be due to vaccine hesitancy but can be explained by well-established theories of human behaviour. The COVID-19 vaccine is a new innovation which targets everyone around the world, and for a relatively new virus. In rolling it out, the government should bear in mind the Diffusion of Innovation theory, which places people on a spectrum, ranging from those who are open to innovation and those who are more conservative, bound by tradition and sceptical of change.

This means that different people will have different perceptions of the vaccine which will affect when they choose, or don’t choose, to vaccinate.

Different strategies are needed to appeal to these various groups. They should include:

- for early adopters of the vaccine, information sheets on the vaccine and where to get it;

- for late adopters, success stories from those vaccinated early and evidence of the vaccine’s effectiveness;

- for the so-called laggards, fear appeals (persuasive messages to arouse fear) can be used. There should also be pressure on them from people in the early and late adopter groups.

The Kenyan government has shown dexterity in implementing the vaccination plan and it’s clear that the exercise is steadily gaining momentum with an increasing number of people being vaccinated each passing week. It needs to continue with this flexible approach, adapting to the situation as it’s developing on the ground and plugging the glaring gaps that have emerged. The vaccine enthusiasm exhibited in places like Nairobi can be harnessed to persuade more people in the next phase when millions more doses become available.

Catherine Kyobutungi, Executive Director, African Population and Health Research Center

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.