Dariusz Dziewanski, University of Cape Town

There are as many as 130 gangs in Cape Town, South Africa. They have the tightest grip on those parts of the city where poverty and insecurity have pushed an estimated 100,000 young men and women into a struggle over identity, interpersonal grievances and drug turf.

Cape Town’s history of gangsterism is rooted in the social disorder that was brought about by white minority rule under apartheid. The city’s gangs later expanded and professionalised after a globalising post-apartheid South Africa connected them to the transnational drug economy.

Gangsters now thrive in the segregated spaces that define the persistently unequal South African urban landscape. For the people living along the margins of Cape Town, joining a gang offsets a lack of development and governance, and helps members access opportunities for self-protection, dignity and income.

Once in, it might feel like there is no way out of a gang alive, a fact seemingly confirmed by murder statistics showing that an average of two lives are lost to gangland killings in Cape Town every day. But gangsters do get out, as chronicled in my new book on gang entry and exit in what has become Africa’s most murderous city.

The book is based on the life histories of 24 former gang members, with hundreds of hours of additional interviews and observation from five years of ethnographic research. It reimagines gangsterism by heeding the difficulties of disengagement, while confirming the possibility of leaving behind crime and violence – even for people facing many disadvantages in life.

Little has been published on gang exit in Cape Town. In an earlier study, I looked at the different stages of role transition gang members move through when shifting from a gangster identity to an ex-gangster one. This book focuses instead on the kinds of cultural learning – skills, tastes, styles, mannerisms, credentials – that ex-members draw on during their exits, when all they have known, for decades sometimes, are criminal networks and gang culture.

Getting in is easy

Joining a gang can seem like a good option for somebody with few prospects of employment, who lives in a neighbourhood with little policing, insufficient public services and inadequate opportunities. Surviving in such a setting calls for toughness. One of my informants, Gavin, put it like this:

You need to be hard like this place to survive here … You won’t show emotions. You’ll kill if you have to.

Gavin controlled drug distribution for his gang, the Mongrels, in several areas. When cunning was not enough, he resorted to conflict – and sometimes murder.

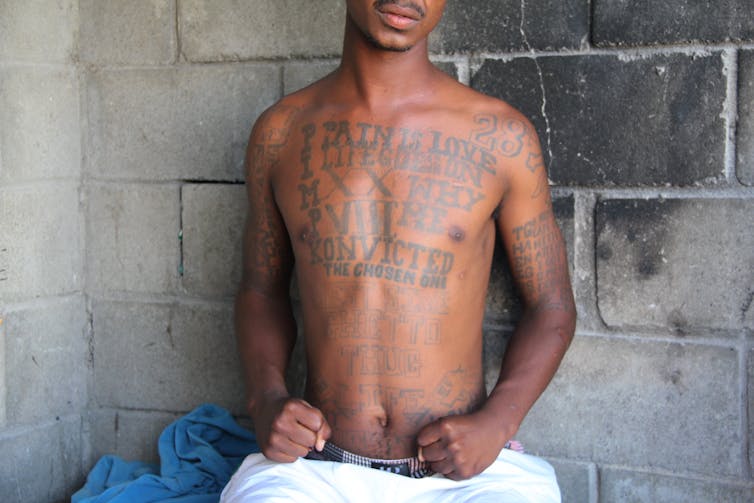

Frequent and ferocious displays of violence are the surest path towards status and authority – “street capital” – for a gangster trying to rule a local drug market. Street capital is a play on “cultural capital”, a concept developed by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu to demonstrate the benefits a person can gain by being familiar with the mannerisms, vocabularies, styles and practices of a particular social space.

Within street culture, risk-taking, bluster and extreme violence are valuable skills and sources of respect, even if they are ultimately self-defeating. A lifetime of pursuing street capital imprints gang tattoos, street slang, puffed-up personas and an erratic demeanour onto hitmen, drug merchants and street soldiers. That makes it less likely they can get a job, keep a healthy relationship or stay out of prison. They’re held captive to socially ingrained habits, skills and dispositions that encourage volatility and violence.

This helps explain why Gavin would join a gang even after witnessing his brother die in gang violence. And why he would waste years in jail for a gang-related murder, seemingly fulfilling the stereotype that either a prison cell or a body bag are the only ways to exit a Cape Town street gang.

Getting out is hard, but possible

But there are other ways to get out and the 24 men and women in my book explained how they did it. Each in their own way focused on creating what they called a “normal life” through some combination of employment, family or religion. Explains Gavin:

In the normal life, you, like, need to be settled, be like any other man, and get married, get children, and work.

Family served as a source of emotional, social and material support. Gainful employment provided income and purpose. Gavin and others also relied on religion for moral guidance, community and resolve.

Being a dedicated employee, a devout believer and a good spouse and parent are personal tools ex-gangsters relied on. These were also outward-facing strategies the book’s protagonists used in order to prove to outsiders – family, neighbours, allies and foes – that their redemption stories could be trusted. A convincing performance of normal living gave them the best chance of keeping alive through the risky early stages of their out-of-gang transitions – when one’s gang history remains hottest to the touch.

Sadly, survival is far from assured. Gavin was shot at and almost killed three times, beaten and hospitalised twice, and stabbed once during disengagement. Eventually he survived for long enough that his enemies finally accepted his change and left him alone.

Gavin faced subtler challenges too. Although he landed a job, he found it hard to adapt to the environment of an upmarket coffee culture café:

Like if I had tik and unga (methamphetamines and heroin), I will know this one is tik and this one is unga. But with the sauces (the café serves), I have to bring you both and just let you choose. And that’s how it moves. It’s like knowing what’s in front of you, but not knowing what it means. So, to adapt is hard.

As the months passed, though, he gained a grasp on the types of insider knowledge – or cultural capital – it took to succeed.

As gang members like Gavin try to master a lifestyle that is less hectic, less bellicose and less ruthless, they not only offer incontestable examples that leaving gangs is possible, but their journeys yield insights that can inform efforts to reduce gang violence. For instance, including and supporting informal mechanisms – family, friends, community and church – in disengagement programming is key.

Gang prevention strategies that rely on hard policing and harsh prison sentences are only likely to undermine rehabilitation and reintegration. They cut people off from their communities, prevent them from finding work and separate them from family. Fighting gangs requires disengagement initiatives that help connect people to non-gang groups and practices, as well as efforts to tackle structural drivers of gang participation, like poverty, inequality, insecurity and exclusion.

Gang Entry and Exit in Cape Town demonstrates that personal transformation among gang members is possible, providing a counterweight to the focus on cycles of poverty, incarceration and violence often found in street cultural writings. Rather than simply reproducing the poverty-crime-violence narrative, the book demonstrates how gang members reorient their lives for the better. Each successful exit is a challenge to the pessimistic conclusions commonly associated with gang life in Cape Town.

Dariusz Dziewanski, Honorary research affiliate, Centre of Criminology, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.