Julius Heise, University of Marburg and Werner Distler, University of Marburg

Ghana’s secessionist conflict is rooted in a system that was meant to promote peace.

Since the advent of decolonisation after World War II, secessionist conflicts have been the main cause of civil wars worldwide. An historical example is the Biafra War (1967-1970). A current one is Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis around the calls for the secession of “Ambazonia”.

Over the past couple of years, Ghana has also been kept on tenterhooks by calls for secession. In November 2019, the Homeland Study Group Foundation declared the independence of “Western Togoland”. Its call was for the secession of Ghana’s Volta region and parts of the Northern and Upper East regions. At first peaceful, this demand led to violence in September 2020 with the emergence of the Western Togoland Restoration Front.

The antecedents of this claim go back over 60 years, and the role played by the United Nations (UN). Prior to Ghana’s independence in 1957, the United Nations oversaw British (Western) Togoland through the International Trusteeship System. This system was created to administer and supervise certain territories. Its aim was to promote development towards independence and to maintain international peace and security.

In a study we conducted, we argue that the UN trusteeship system after World War II had the unintended effect of perpetuating secessionist conflicts. Colonial powers framed secessionism as a threat to state-building – not as an expression of self-determination. We looked specifically at the Ewe/Togoland unification conflict in the bordering regions of the British Gold Coast and the trusteeship territories of Togoland.

Our analysis leads us to caution against a rhetoric that polarises the issue in terms of “threats”.

A history of distrust

International intervention by the UN is generally supposed to provide a peaceful solution – not the perpetuation of conflicts. But historical research using colonial archives and UN documents points to precisely such a pattern. A significant number of the former 11 UN trust territories in various parts of the world experienced some form of secessionist conflict.

The UN trusteeship system was by no means a venue of tranquil diplomacy. Rather, it involved a politically heated negotiation process between the UN, its trustees and national elites.

The Western Togoland secessionism fits this pattern too. Many of the actors involved in the system attempted to escalate, de-escalate or ignore conflicts around the separation of Western Togoland from the erstwhile Gold Coast. They used a mode of conflict communication called “securitisation”. This involves reframing an issue as a security problem to gain room for manoeuvre and push through more far-reaching, controversial measures politically.

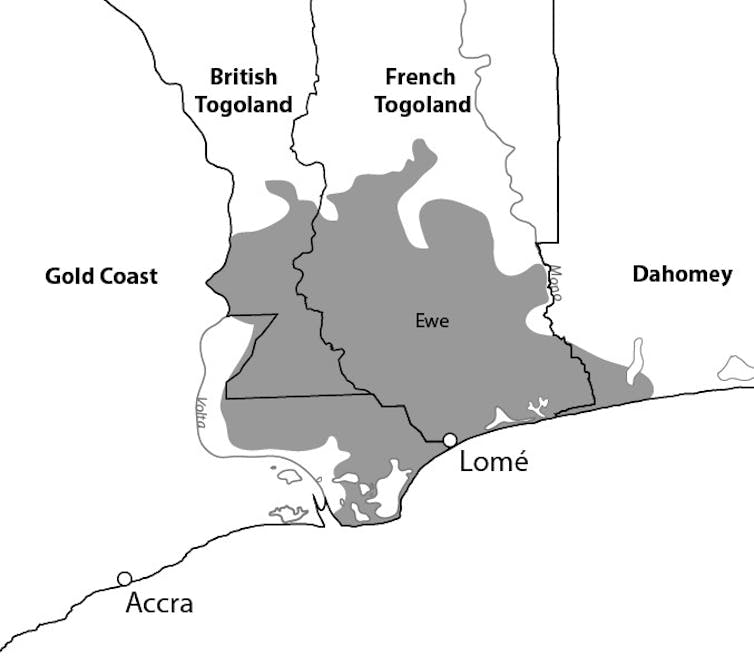

When France and Britain divided up German Togoland after World War I, the new colonial demarcation separated the Ewe-speaking population into three territories. These were the British Gold Coast Colony, British Togoland and French Togoland. A movement then formed to campaign at the UN for the political unification of the Ewes.

Unwilling to cede territory, France and Britain pointed out the dangers of balkanisation“ to the UN. Allowing the Ewes to decide on unification would implicitly give them the right to secession. It would create an incalculable domino effect by setting a precedent for numerous other dependent territories whose borders had been drawn arbitrarily.

The UN itself reported in 1949 that in the interest of peace and stability a solution should be sought with urgency. In view of France’s and Britain’s reluctance to consider the Ewes’ demands, representatives of the anti-colonial UN member states cautioned that their nationalistic clamour was a danger to peace in West Africa.

Faced with the apparent futility of Ewe unification, the movement shifted in the early 1950s to the more promising reunification of French and British Togoland. Its supporters pursued a strategy of pointing to human rights violations, which discredited the French in particular. While anti‑imperial UN member states acknowledged the problem, the permanent members of the Trusteeship Council did not seriously consider Ewe or Togoland reunification.

In 1956 the UN-supervised referendum sealed the incorporation of British Togoland into the Gold Coast. Those in support of unification then asked the UN as the “world peace organisation” to revise the result, or at least consider the electoral districts separately on the grounds that there could be “serious unrest” or an “ultimate war”.

Overruling the request, the UN followed the wishes of the colonial authorities. It framed secessionism as a “threat” to state-building rather than an expression of self-determination.

By curbing secessionism during the period of decolonisation, the UN laid the foundation for it to escalate again later. The issue of Western Togoland fortunately never turned into a full civil war. Nevertheless low-level violence and political conflicts remained. The 1957 Avoidance of Discrimination Act and 1958 Preventive Detention Act practically outlawed Togoland secessionism overnight. It revived only briefly in the mid-1970s, and seemed to have disappeared until recently.

Changing legacies

The long history of the conflict around “Western Togoland” illustrates two points.

First, the vocabulary of international law and the UN implies a clear meaning of terms such as self-determination or decolonisation. In reality, the specific meanings in the decolonisation period were shaped by the perception of whose self-determination was seen as a threat to the international order. Secessionist movements and territorial changes could easily be portrayed as an overriding threat to the state and regional order and therefore considered illegitimate.

Secondly, the introduction of the right to self-determination by the UN in 1952 led to new conflicts over secession, a very real legacy of colonialism and the UN trusteeship system. The UN, with no genuine answer as to who could claim independence and how, adhered to colonial borders.

Both points led to the fact that in Ghana, almost 60 years after independence, the conflict over “Western Togoland” does not seem to have been resolved.

Politicians and security analysts have joined the securitisation of the secessionists and called for heavy-handed solutions. But the past shows that this kind of rhetoric might solve the issue in the short term but not in the longer term.

A public dialogue that avoids portraying the other side as a threat would be more likely to succeed in settling the conflict once and for all.

Julius Heise, Research Fellow, Center for Conflict Studies, University of Marburg and Werner Distler, Research Fellow, Center for Conflict Studies, University of Marburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.