Anine Kriegler, University of Cape Town

The double-digit increases in South Africa’s recently released quarterly crime statistics are eye-watering, but they do not mean crime is spinning out of control or “soaring”. They need to be put in context.

There were bound to be more crimes recorded between April and June 2021 than between April and June 2020, when the stay-at-home order and alcohol ban due to the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in an exceptional reduction in crime.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which has put the country under lockdown for 17 months, since 23 March 2020, has had a complicated impact on crime levels. First, it has expanded the range of laws that can be broken.

For instance, on the first day of the nationwide lockdown, there were 55 arrests for contravention of the regulations of the Disaster Management Act. In the little under a year that followed, there were over 400,000 more arrests, for such new offences as violating curfew and breaching gathering rules.

Although anecdotal reports are that few of these cases were prosecuted, some of them probably did result in otherwise law-abiding people getting a criminal record.

It is almost certainly the case that the focus on enforcing compliance with lockdown regulations distracted the police from other public safety priorities. This might be expected to lead to an increase in ordinary crime. Instead, many countries around the world recorded dramatic declines in crime under lockdown. South Africa was among them, with major reductions across most crime types, at least under the “hard” (level 5) lockdown from 27 March to 30 April 2020.

This is largely due to a shift in lifestyles. People who never leave the house provide potential criminals with few opportunities for interpersonal crimes like assault or street robbery, and rarely leave their homes unguarded and vulnerable to burglary.

It’s known that places with more stringent stay-at-home measures saw larger declines in crime. But in some places there has been a surge in crimes in the home, such as domestic violence and child maltreatment.

This does not seem to have happened in South Africa, maybe because the ban on alcohol sales reduced the severity of domestic violence cases.

The booze bans

This is the second likely reason for the decrease in crime in South Africa over the COVID-19 period. In addition to the typical measures taken in other countries to limit the spread of the disease, the government imposed restrictions on alcohol sales. This was done because of the role that alcohol plays in undermining social distancing, compromising immune response and contributing to the volume of trauma cases in hospitals.

There have been numerous complete bans on alcohol sales, and partial restrictions by day and time of permitted sales.

The impact on trauma admissions at South African hospitals has been remarkable. Reduced alcohol consumption, especially among heavy or problem drinkers, can also lead to a general reduction in crime by reducing the likelihood that disagreements escalate into assaults, and reducing potential victims’ vulnerability to predatory crimes.

Tracking the stats

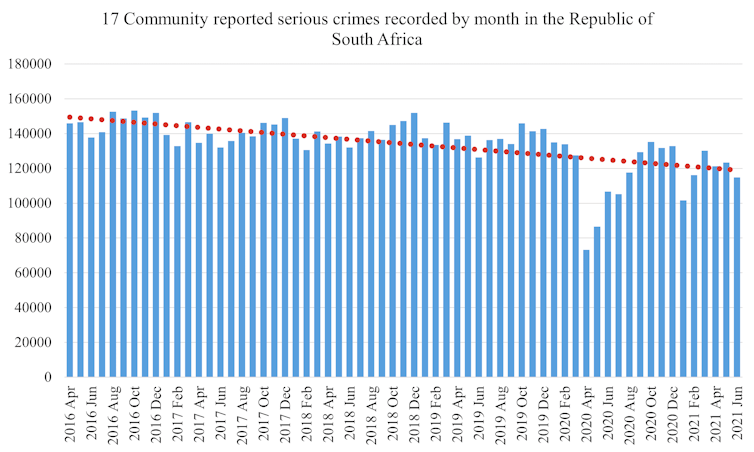

The impact of the lockdown and liquor restrictions can be seen in the latest official crime statistics. Recorded monthly crime figures across various crime types show that the period of April to August 2020 was one of exceptional decrease, but that they have now returned to their pre-pandemic trajectories.

The 17 so-called community reported serious crimes are all those which are brought to the attention of the police by victims or witnesses. This includes violent and property crimes, but excludes the “victimless” crimes that police must usually seek out themselves, such as driving under the influence of alcohol.

The graph shows a gradual downward trend, decreasing by 13% from April 2016 to the 127,555 recorded in March 2020. Then the lockdown is imposed and there is a sharp decrease of 43% to 73,190 in April 2020, followed by a recovery over the next five months. There is a dip again of 24% in January 2021, during the third alcohol ban.

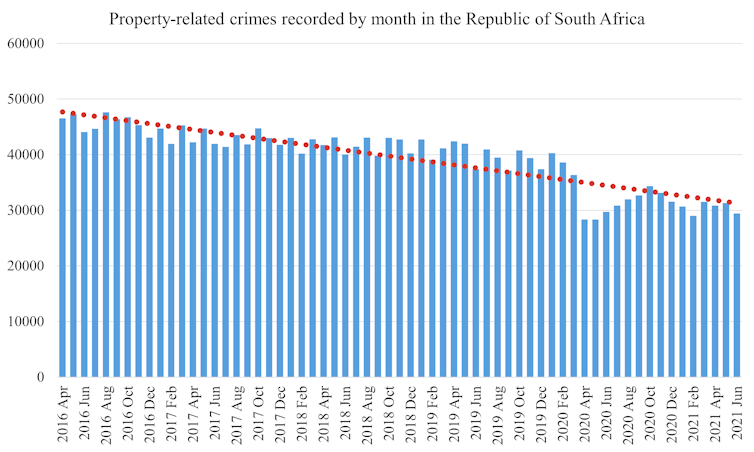

The extent of the lockdown effect varied by crime type. Property-related crimes are those that do not involve direct contact between victim and perpetrator, namely burglary at non-residential premises, burglary at residential premises, theft of motor vehicle and motorcycle, theft out of or from motor vehicle, and stock-theft.

The number of property-related crimes declined by 22% from April 2016 to the 36,355 recorded in March 2020. The decline during the hard lockdown period was less dramatic, at 22%. The decrease during the January booze ban was also relatively minor, at 3%.

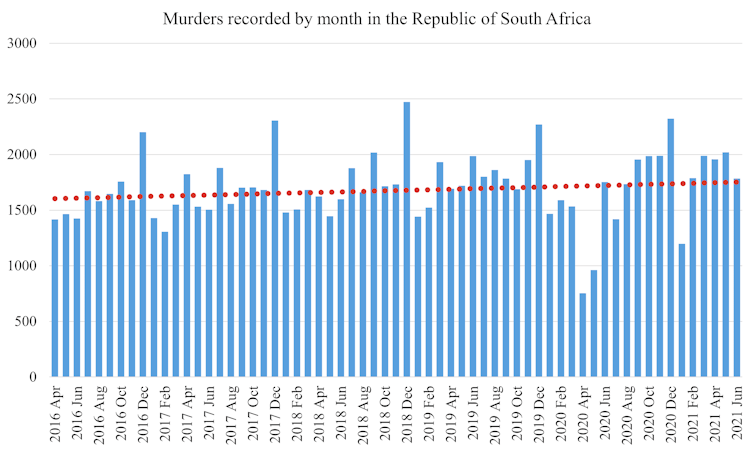

By contrast, murder figures increased by 8% from April 2016 to a total of 1,534 in March 2020. This is particularly worrying because murder figures are a relatively reliable indicator of real murder levels, whereas a smaller and more variable proportion of other crime types make it into the official stats.

The murder figures show a clear seasonal pattern, with a spike every December.

The lockdown decline was considerably more dramatic for murder than for property-related crimes, dropping by 51% between March and April 2020, to 752. The murder figures also suggest a more important role for alcohol. There is an increase in the month of June, when alcohol restrictions were briefly relaxed, and another sharp decrease of 48% during the January booze ban.

Back to ‘normal’

South Africa’s latest crime statistics do not show a sudden escalation in crime. Instead, they show a return to the trends seen before this exceptional period of lifestyle disruption. But this should not lead to complacency. Levels of crime, especially violent crime, are still among the highest in the world. The national murder rate is about six times the global average.

The answer to crime is not to permanently lock everyone in their homes or ban alcohol for good. But this does seem to be a good time to consider less intrusive public health measures to curb excessive alcohol consumption.

Anine Kriegler, Postdoctoral fellow, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.