Fiona Woollard, University of Southampton

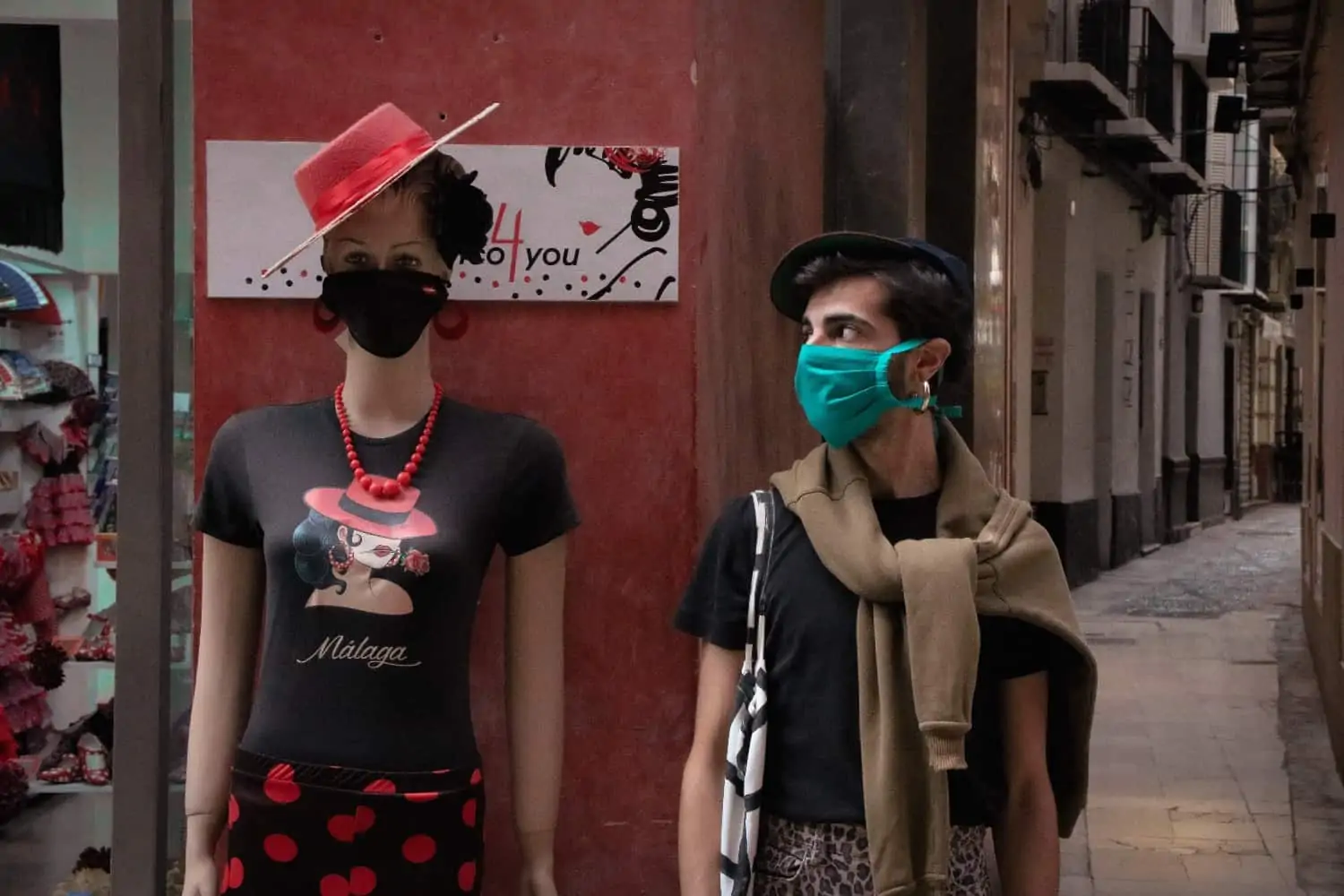

Most people in the UK plan to keep wearing masks on public transport or in crowded indoor areas to avoid spreading COVID-19. However, when mask mandates lift – as they have done largely across England – some people say they will no longer wear one if they don’t have to.

Everyone in a crowded indoor area should wear a mask if they can. It’s something we do for others: it reduces the chance of causing serious harm by giving somebody the coronavirus, which you might be inadvertently carrying despite not having symptoms. Put simply, you need to wear your mask to protect me, and I need to wear my mask to protect you.

But mask wearing is also something that many people feel very strongly about. Confronting someone about it could make them upset or lead to an altercation. We also need to take care that we aren’t demanding that people share personal information with us to explain why they aren’t wearing a mask.

With that in mind, here’s how to go about talking to people about mask wearing in the right way. Discussions are likely to go best if we can frame mask wearing as something that’s done for the benefit of others, while avoiding blame or shame.

When to ask someone to wear a mask

Reasonable expectations about mask wearing need to be carefully balanced with respecting others’ privacy. You do not want to mount a one-person crusade to call out every person who does not wear one. It is often better if we can rely on reminders to suggest mask wearing – such as notices – that do not interrogate or single anyone out.

There are some people who cannot wear a mask for health or other personal reasons. When masks were legally required across the UK, the government recognised several exemptions – circumstances when wearing a mask is required.

For instance, people may have physical or mental illnesses, impairments or disabilities that mean they aren’t able to put on, keep on or take off a mask. In some cases, wearing a mask would cause great distress.

You cannot tell whether someone has an illness or disability just by looking at them. And you cannot see whether wearing a face covering will trigger someone’s memories of violence or abuse. We’re not entitled to demand that people share this personal and private information to explain why they are not wearing a mask.

Therefore, if you see someone who isn’t wearing a mask, and you don’t know why, you shouldn’t go up to them and tell them to wear a mask or ask why they are not wearing a mask. Some people have good reasons not to.

This is why it is helpful if there are notices in public places stating that everyone who can wear a mask should do so. They remind us all to wear masks but do not invade anyone’s privacy.

But sometimes there is something that singles a person out for you, giving you a more personal interest in whether they are wearing a mask. It might be that someone is coming into your home or looking after your children. They might be someone who is standing or sitting very close to you without a mask on. In such cases, it is reasonable to ask them to wear a mask if they can.

How to ask someone to wear a mask

If you don’t know why someone isn’t wearing a mask, but you’re in a situation where you need to talk about mask wearing, you can respect their privacy by explicitly making clear that your request is conditional: you can ask them to wear a mask if they can.

Be clear that you are asking them to wear a mask to protect you and (if present) your children. This may raise the chances of your request being effective. Research into health messaging suggests that campaigns that focus on the need to protect others are more likely to be effective.

But – be careful when appealing to people’s morals. If someone feels they have a moral duty to do something, their failure to do it can make them liable to feeling guilty, shameful and blamed. So if confronted about not wearing a mask, and yet feeling that they ought to, they may try to avoid these negative emotions by refusing to listen or trying to show it is the other person who is in the wrong. Trying to change behaviour through shaming people, in particular, has been shown to backfire.

You want to appeal to shared values and shared concerns while explicitly avoiding any suggestion you see the person you are speaking to as a bad person. If they are close to you, remind them that they are a great relative or friend and that you know they would never want to harm you and your family.

Fiona Woollard, Professor of Philosophy, University of Southampton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.