Andrea Janku, SOAS, University of London

This month the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is celebrating its 100th anniversary. It has come a long way from its secret beginnings in July 1921, when 12 delegates from a small number of study groups of ardent young Marxists gathered in Shanghai for their first national congress.

These groups emerged from the anti-imperialist and nationalist protests of May 4 1919 that had merged with a larger social and cultural movement. In an intensely international intellectual environment young students sought radical change and found inspiration in a range of new ideologies, from liberalism, humanitarianism and individualism to anarchism, feminism and socialism.

After the success of the Russian Revolution in 1917, Marxism gained significant traction. The Moscow-based Third Communist International offered support and sent a representative to the Shanghai meeting. The CCP thus emerged from a combination of the anti-imperialist and nationalist impulses of the May Fourth Movement with – as American scholar Maurice Meisner puts it: “The chiliastic [millenarian] expectations of an imminent international revolutionary upheaval inspired by the writings of Lenin and Trotzky.”

How does one square this youthful rebelliousness with the situation today where the party has a membership of more than 90 million and is ruling over the world’s largest population. A party that has opened itself to private businesses, with the result that aspiration to membership is largely a career decision?

Creating a revolutionary tradition

At the beginning of 2021, the Ministry of Education launched an educational campaign with the aim of bolstering young people’s allegiance to the party. In an international environment where China is under intense pressure to justify its increasingly relentless authoritarian stance, this campaign is the expression of a deep anxiety about the preservation of the party’s revolutionary credentials and political legitimacy.

The preservation of “the red genes” lies at the heart of this campaign, as shown in this analysis by the China Media Project: Our Colour Must not Fade. Back in January 2021 the Ministry of Education issued guidelines on how to inculcate the revolutionary tradition into the minds of young children through the primary and secondary school curriculum.

This was followed by further instructions on how to teach children from a young age to “follow the party forever” using a series of tools from short video clips to class assemblies celebrating the “party spirit”, to patriotic education through red tourism.

The study of Xi Jinping’s New Era Thought is seamlessly brought together with a party/state history that focuses on the establishment of the “New China”. In this narrative, “New China” begins with the glorious foundation of the People’s Republic in 1949. China’s development is tracked through the “Reform and Opening” policies launched in 1978 that “opened” China to the world after the end of the Mao era, to its reconstitution as the major global power that it is today.

Conveniently brushing over the disasters of the Mao era, such as the purges of “rightist” intellectuals, the famine of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, these new guidelines aim to make children from primary school age to “unswervingly obey the party”.

Xi wants to go back to the revolutionary roots of his party without the social turmoil attached to it. The exact opposite of a revolution.

The century of youth

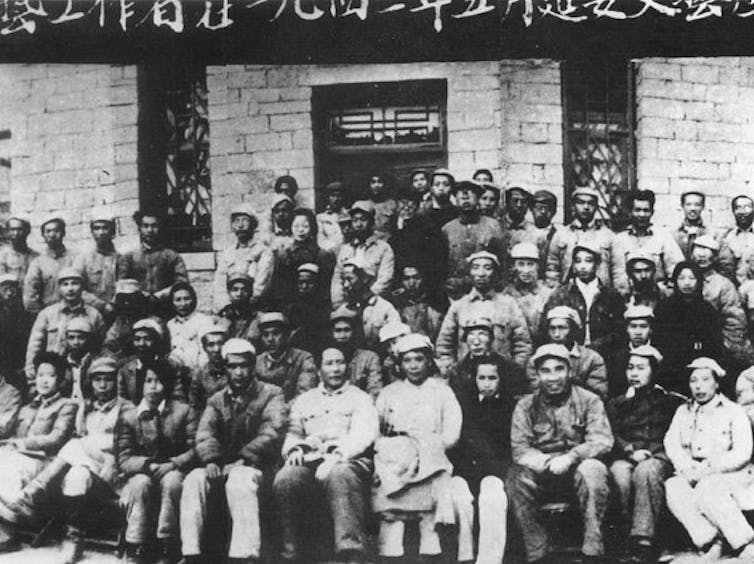

Party propagandists know why they focus on young people. It’s the youth that are uncompromising, daring and hungry for change. But it’s also the youth that tend to hold authorities to account – and therefore need to be brought in line. This part of the revolutionary tradition was shaped in the Rectification Campaign of 1942 in Yan’an, a remote corner of the country, where the embattled communists had built their new base.

In March of that year, Wang Shiwei, a freethinking writer who would become one of the most tragic victims of this campaign, published his essay, Wild Lilies – the work that would bring him into trouble. Its opening lines told about Li Fen, a young student at Beijing University in 1926 where she joined the Communist Party. With great affection, sadness and admiration Wang describes Li’s courage and determination when she faced a martyr’s death upon being betrayed to the authorities by a member of her own family only two years later.

The purity of the youthful martyr stands in stark contrast to the hypocrisy of the elitist party leadership in Yan’an. In Wang’s mind, what was dismissed by some as youthful grumbling over minor injustices – such as unequal access to food and women – diminished and mocked the sacrifices made by young idealist revolutionaries such as Li. He wrote:

The potential value of youth lies in its purity, sensitivity, fervour and love of life. When others haven’t felt the darkness, they sense it first, when others are reluctant to utter the unmentionable, they speak out courageously.

Wang saw in youth – as embodied by Li – a heightened perceptiveness, a strong sense of justice and greater willingness to stand up for their ideals. The celebrated author Ding Ling’s exposition of gender inequalities, criticising the party’s double standards when it came to women’s emancipation, was a more prominent example of the same.

The fates of both were in different ways signs of things to come and set the tone for the political campaigns and purges of the following decades. Wang spent the next years in confinement and was executed in 1947. Ding retracted and became a lauded author of social realism.

Wild Lilies highlighted the deep chasm between the idealism and the sacrifices made by women like Li and the betrayal of those values by the privileged leaders of the revolutionary society in Yan’an. What remained of the May Fourth rage was soon drowned in ideological struggles and Leninist party discipline. Ding lived, but her literary creativity was essentially stifled.

Mao would later use the power of the youth to turn against his own party, when he launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966 in a desperate attempt to reassert his position of power. The Cultural Revolution was the spectre that was evoked to justify the brutal crackdown when young students initiated the social protest movement of the early summer of 1989 leading to the tragedy of Tiananmen Square. Students have also been the main force behind the recent protests in Hong Kong.

The 100 years of the CCP’s history are full of ambiguities and contradictions, hope and joy, suffering and despair. There is a lot that is worth remembering. But the inculcation of a streamlined revolutionary tradition in an attempt to create new generations of blindly obedient followers is likely to backfire.

Andrea Janku, Lecturer, Department of History, School of History, Religions & Philosophies, SOAS, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.