With many mutations, such as is the case with the new Omnicron variant, a more heterologous vaccine strategy has been experimented with. And not only does research suggest that it will work but it also means that vaccine distribution could become less of a problem.

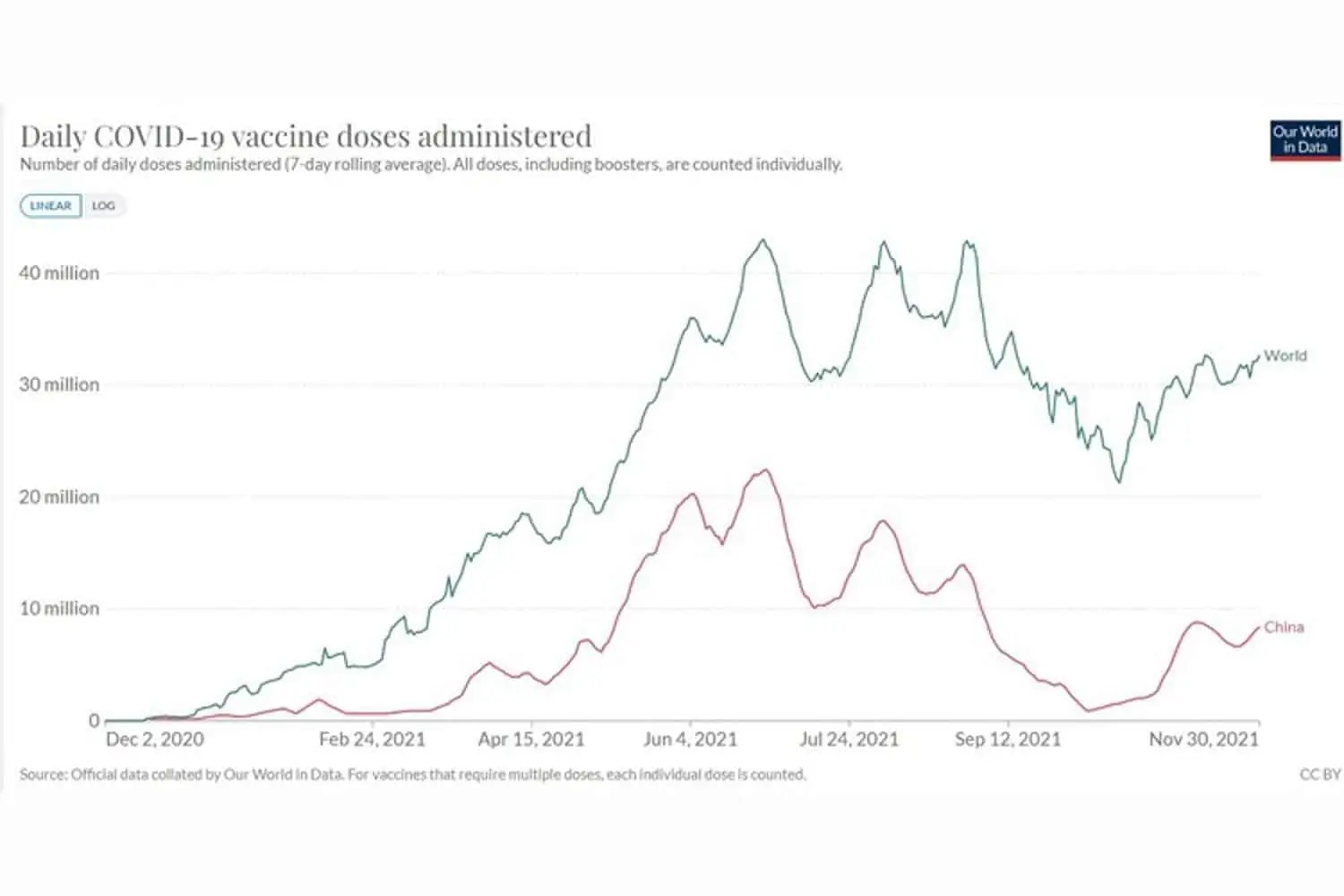

China is the world’s largest exporter of Covid vaccines. As of early November it had exported some 1.5 billion doses. Those exports are dwarfed by China’s domestic consumption, with 2.5 billion doses administered.

A total of 8 billion vaccine doses have been administered worldwide, so China has used over 30% of all doses and manufactured roughly half. The chart of global vaccine administration reveals a simple fact; when China’s vaccination capacity is under-utilised, global vaccine rollout slows. (See graph at top of article.)

The fastest route to accelerated global vaccination, and to ending vaccine inequity, is to use this enormous manufacturing capacity efficiently.

The Chinese vaccines have been viewed as less desirable than their Western counterparts, particularly the highly-coveted mRNA vaccines. This is due in part to lower efficacy – Sinovac’s efficacy at preventing infection was reported by the World Health Organisation as 51%, which is the lowest reported of any of the vaccines on the market. Sinopharm’s efficacy was reported as 79%, superior to Oxford-AstraZeneca, and to the single-dose Johnson and Johnson vaccine, but still far short of the >90% efficacies initially reported for the mRNA vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna). This apparent shortfall in efficacy can, however, be addressed by way of a heterologous booster shot (using a different vaccine for the booster).

Mixing vaccines: research shows it works

Chile has trialled a range of heterologous vaccine strategies, an astonishingly valuable program of research which serves as a roadmap for efficient vaccine utilization.

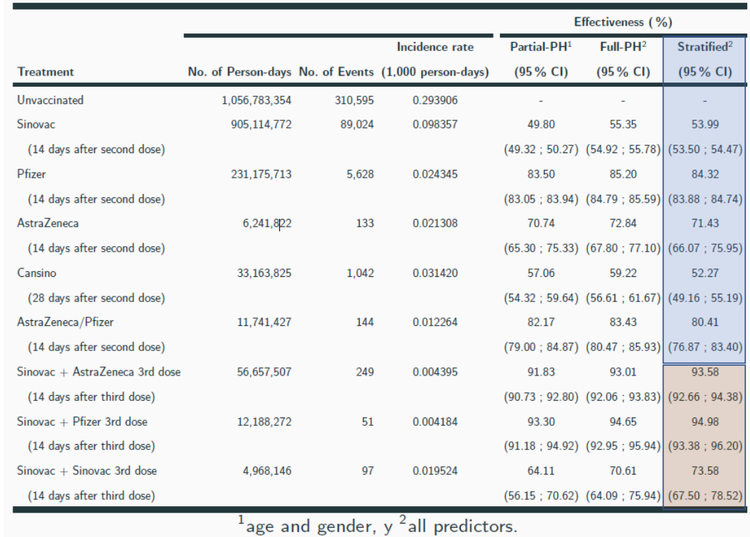

Results of heterologous testing strategy in a study in Chile. Source: Covid-19 Vaccine Effectiveness Assessment in Chile

Following this research Chile has widely rolled out a heterologous strategy using two doses of Sinovac as the primary dose series, followed by a Pfizer shot, with findings indicating that this strategy produces superior immunity to a standard two-dose series of Pfizer or to a three-dose series of Sinovac. They found that three doses of Sinovac resulted in 71% protection, compared to 93% for the 2:1 dose ratio heterologous series.

A three-dose series of Pfizer was not tested, but a two-dose series of Pfizer had 81% efficacy in the Chile trial. Research has shown that the third Pfizer dose results in very highly increased protection compared to the second. Nevertheless, even if a three-dose series of Pfizer were to provide 100% protection, applying a straightforward calculation shows that a strategy that vaccinated a third of a population with three doses of Pfizer and the other two-thirds with three doses of Sinovac would confer an average protection of 81%, compared to 93% from using the heterologous strategy for the entire population. This calculation is of course quite limited in its scope, being limited to the study’s primary endpoint of prevention of infection 14 days after final dose, but it does demonstrate the potential for heterologous strategies to obtain better overall protection from a given set of available vaccines.

Sinopharm’s vaccine was not tested, but it is of the same type as Sinovac, an inactivated whole virus vaccine, and is likely to have a similar response.

Mixing vaccines can lead to more equitable distribution

The 2:1 dose ratio of this heterologous vaccination protocol happens to quite closely match the ratio of current manufacturing capacities, suggesting that this protocol is a particularly efficient strategy for global vaccine production.

Here is an example of how cooperation between countries could improve vaccine distribution: South Africa has declined delivery of Pfizer doses, due to slow vaccine rollout not keeping up with delivery rate. Those doses are likely to be donated to other African countries. But there are other countries, particularly in South America, that are highly vaccinated with Sinovac and in need of Pfizer vaccines for boosting. If South Africa were to exchange two thirds of its Pfizer doses for Sinovac doses, on a 2:1 basis, and then donate the resulting heterologous dose sets, greater protection would be achieved in both the African and South American nations.

Moreover, any country currently using a homologous strategy of over-subscribed vaccines could contribute to addressing vaccine inequality by switching to heterologous strategies that utilise under-subscribed vaccines. This would not only increase the average protection achieved per vaccine dose, but also increase the total number of doses that can be administered by better matching uptake and production.

Omicron makes the case stronger

The emergence of the Omicron variant strengthens the case for this approach, for two reasons. The first is that it has a high number of mutations in the spike protein which experts anticipate will give it a high degree of immune escape from existing vaccines and perhaps from immunity arising from prior infections.

The Chinese vaccines are the only widely-used ones currently on the market that expose the immune system to the entire virus rather than just to the spike protein, and they have been confirmed to result in a broader immunological response. It is likely that the immunity conferred by these vaccines, while weaker in absolute terms, will be somewhat less affected by changes in the spike protein specifically. Because Covid’s mutations take place primarily in the spike protein, this would be of benefit as new variants continue to arise.

On 8 December a number of laboratories globally began releasing the results of studies of vaccine efficacy against Omicron. Despite the fact that the Chinese vaccines comprise half the doses administered globally, none of the studies released so far has included either of them, a glaring omission that delays our understanding of how Omicron will interact with vaccines that half the world has used.

Omicron will change the face of global vaccination efforts in another profound way. The concerns raised by experts over its possible antibody-escaping nature have prompted Moderna and Pfizer to announce efforts to update their vaccines specifically for this variant.

Pfizer’s CEO has indicated that updated vaccine candidates could be ready in 100 days. This capacity for rapid modification is one of the strengths of the new mRNA vaccines, compared to older types of vaccine, and is highly promising for our ability to respond quickly to mutations, but it does have some ugly implications. The first problem is that the mRNA vaccines are already over-subscribed and demand for updated ones will worsen that.

The second is that clinical trials for a booster shot will be far quicker than trials for a full primary series trial of two or more doses, because of the necessity for a delay between primary-series vaccine shots. What this means is that regulatory approval for the booster shot will likely precede approval for a primary series by a lengthy period. The implications of this are unsettling; there will be an updated vaccine for the Omicron variant but it will only be accessible to those who are already vaccinated. This situation threatens to further deepen vaccine inequality.

The 2:1 heterologous strategy somewhat alleviates this situation by using currently under-used manufacturing capacity to deliver a primary dose series with the potential to follow up with an Omicron-specific booster later. Currently, there is a lull in uptake of the Chinese vaccines, which are being administered at a rate which is 14 million doses per day lower than the previous peak. Using those readily-available doses now, and following up with mRNA vaccines later when they become available, will better match uptake to availability.

In short, moving to heterologous vaccination strategies using under-subscribed vaccines will increase the total number of vaccines delivered as well as the average protection per vaccine. This is applicable to countries that are currently highly under-vaccinated, but also to countries with good vaccine access that are currently committed to homologous strategies using over-subscribed vaccines. Hence, vaccine equity activism could be usefully directed toward encouraging this uptake strategy in both of those settings.

An obstacle to be overcome in pursuing this is poor perception of the Chinese vaccines. This is rooted only in part in lower reported efficacy of the Sinovac vaccine compared to its Western competitors; there are most certainly elements of anti-Chinese prejudice involved in the perception of these vaccines.

To be clear; both of these vaccines have been independently tested outside of China, with the results verified and approved by the WHO as well as a number of other regulatory bodies, including South Africa’s own SAHPRA. Sinovac’s modest efficacy at preventing infection in trials, just 51%, still corresponds to strong protection against severe illness.

Sinopharm, on the other hand, had efficacy of 79% as reported by the WHO, which places it above the prominent Western-made vaccines Oxford-Astrazeneca and Johnson and Johnson.

The following are crucial steps to effectively pursue vaccine equity: de-stigmatising Chinese-manufactured vaccines; recognising China’s significance as a vaccine manufacturing base and the corresponding implications for its role in the current state of vaccine inequity as well as its potential role in ending it; encouraging optimised uptake of heterologous vaccination strategies that use under-subscribed vaccines; making better use of Chile’s excellent research on heterologous vaccination strategies; undoing the harmful narrative that only Western interventions can address vaccine inequity; and further incorporating the Chinese-manufactured vaccines in research efforts.

Earlier this week, China pledged one billion vaccine doses to Africa, which highlights the need for these steps. Destigmatising those vaccines will be necessary to ensure good uptake across the continent, and optimised heterologous use will be required to achieve robust protection, particularly in the face of Omicron and any subsequent variants that may emerge.

The author is a scientist in Wits University’s Chemical Engineering department. Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s