Neal Robert Haddaway, University of Johannesburg; Joe Duggan, Australian National University, and Nicholas Badullovich, Australian National University

As the climate changes, negative environmental effects are being felt and seen around the world.

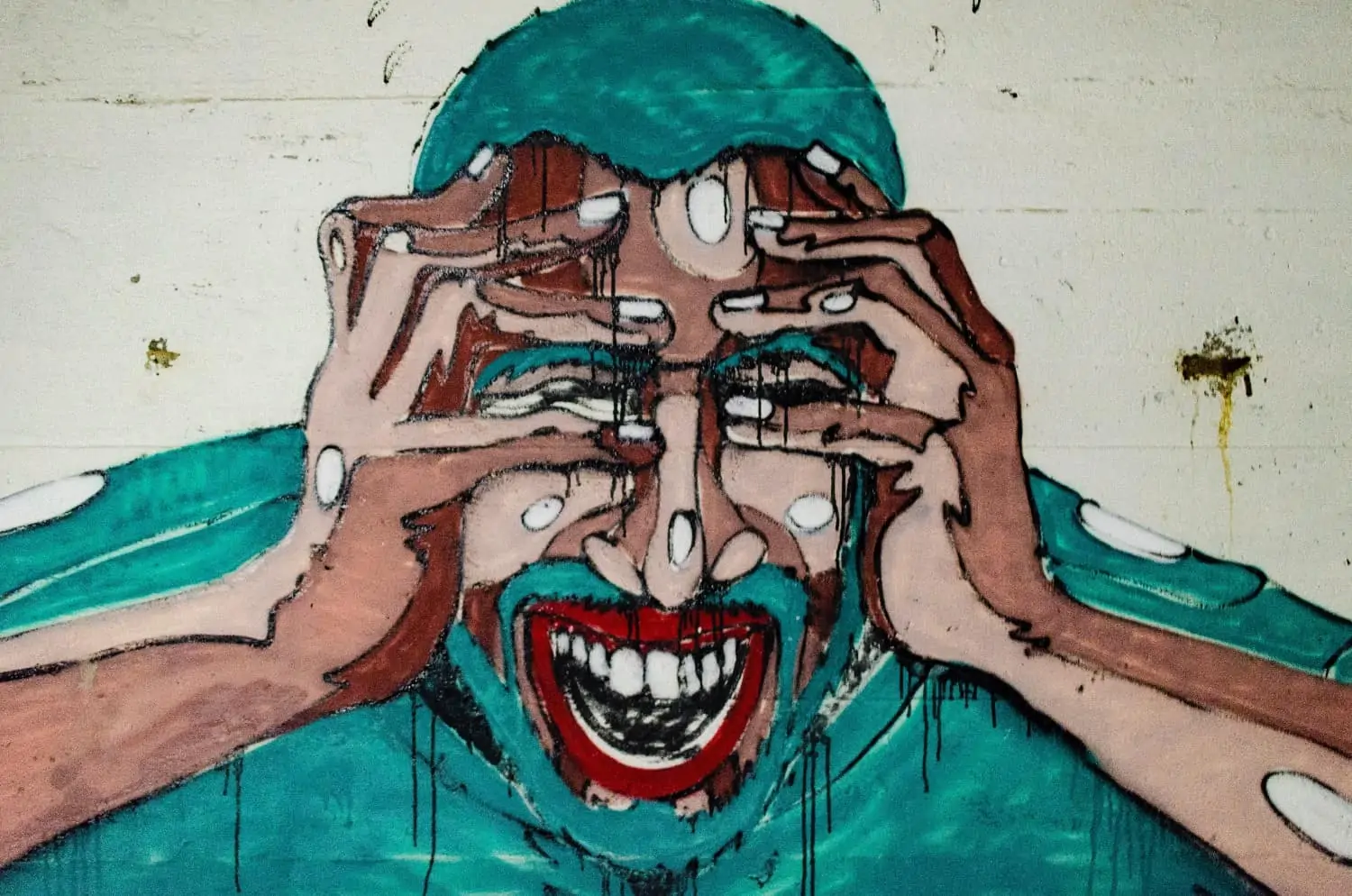

The effect that climate change has on mental health is less immediately obvious or visible. Often termed climate anxiety or eco anxiety, this feeling can manifest as what the American Psychological Association and others describe as a “chronic fear of environmental doom”. Recent studies have shown it is being felt by young people all over the world, as well as by a significant number of adults.

What about the people who explore the data, build the models and quantify the impacts and flow on effects of climate change? How do they feel?

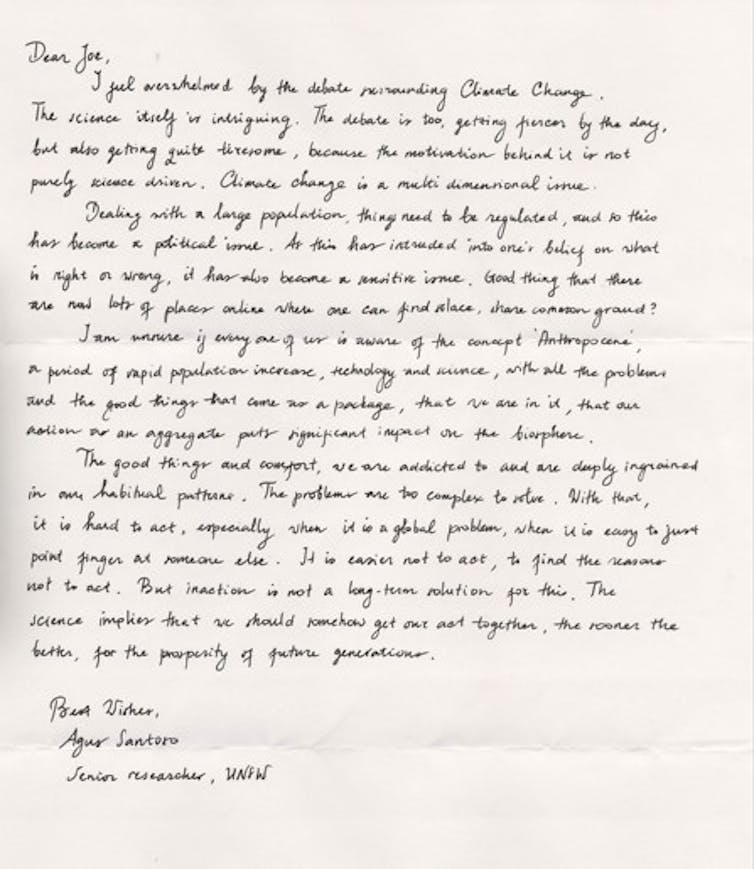

We explored some of the answers in two projects that we have just analysed in an article for The Lancet Planetary Health journal. One project asked climate scientists to describe their feelings about climate change in hand-written letters. The other was a photographic project: environmental researchers were photographed while describing their feelings about the state of the planet.

We found that scientists were experiencing diverse, complex, and often contrasting emotions about the fate of the planet. Their feelings echo those of non-scientists and can be overwhelming, whether negative or positive – but they can also, we believe, be harnessed to create spaces where people can talk honestly and openly about their fears and about potential solutions. This matters because, if we don’t talk, we risk increased feelings of isolation that can lead to helplessness and inaction.

‘Is this how you feel?’

Between 2014 and 2020 one of us, science communicator Joe Duggan, approached climate scientists around the world and asked them: “How does climate change make you feel?” He collected their responses in the form of short, hand-written letters. Five years after the initial “Is this how you feel?” project launched, he returned to some of the original contributors and asked them the same question. These letters were shown in galleries and housed online.

As part of our Lancet article, we analysed the letters for their emotional sentiment.

When analysing all the letters submitted throughout the life of the project, it became clear that climate scientists feel many emotions about the climate, some negative and others positive.

The negative emotions were more frequent, with participants identifying feelings such as “distress”, “anger”, and “upset”. Initially, “hope” appeared as the most frequent positive emotion. However, the more we looked at this, the clearer it became that feeling hopeful about the future was not always a simple, positive emotion. Two key types of hope were displayed: “logical hope” and “wishful hope”.

Logical hope had reasons: “we can be hopeful, because we are seeing (various positive) changes”. Wishful hope went with more negative statements and a desire for future change.

In the other project that informed our paper, “Hope? and how to grieve for the planet”, Neal Haddaway photographed environmental researchers while interviewing them about their feelings on the state of the planet; each participant chose three words to describe their feelings. Their words matched closely the findings from our analysis of “Is this how you feel?”.

Harnessing anxiety

It seems many people, experts and otherwise, have complex emotional responses to climate change. So, why does the emotional response matter and what should be done about it?

Some have provided practical solutions to climate anxiety: things you can do on an individual level to reduce your footprint. Others call for disruptive protests to raise awareness of these issues and force political change. These are vital responses to environmental crises, but they miss a very important part of dealing with anxiety: how people choose to understand, accept and live with their emotions.

Climate anxiety, or any range of emotions over climate change, is not necessarily a bad thing. But the way you feel does not need to define the way you choose to act.

Many people may fear the rise of “doomism” – the feeling that taking action against climate change is pointless. But it is not too late to make a difference, and many emotions, even anxiety, can lead to positive action.

Instead of assuming that our anxiety will go away if we act, or assuming that embracing anxiety means accepting the planet’s fate, we advocate for the creation of more safe spaces, platforms free of judgement with expectations of respect and a willingness to listen, where feelings can be shared and heard. In doing so, society can begin cathartic conversations, validate people’s feelings, realise we are not alone, and foster a sense of community.

Many of the scientists who contributed to both projects said this was the first time they had been asked how they felt about climate change. Spaces for their feelings are important, too, to address and minimise doomism and empower scientists to continue their research – and, perhaps, even to hope.

Neal Robert Haddaway, Senior Research Fellow, Africa Centre for Evidence and Stockholm Environment Institute, University of Johannesburg; Joe Duggan, PhD Candidate, Australian National Centre of the Public Awareness of Science, Australian National University, and Nicholas Badullovich, PhD candidate, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.